Proudly Canadian

Richard Reznick

|

In October 2009, at the annual

congress of the American

College of Surgeons, Robin

McLeod, a Regent of the ACS,

organized a symposium on the

Canadian Health Care system.

The room was packed, predominantly

with American surgeons.

By coincidence, as we

were speaking, the U.S. Senate

was voting on Obama's health care reform bill.

The speakers, Rich Finley from the University of

British Columbia, Bill Fitzgerald President of the Royal

College, Hugh Scully from University of Toronto and I

were poised for a backlash of anti-Canadian health care

sentiment. After all, these past few months have seen a

lot of scare-mongering propaganda, such as rumours of

Canadian Death panels (1) and claims that Canadian doctors

are deserting the profession en masse (2).

To our amazement, the reception we received was exactly

the opposite. Our surgical colleagues were profoundly

interested in our comments, by and large not very

knowledgeable of our system, and somewhat in awe of

the messages they received. Without question, most in

the room left with what we believe is the right information;

that Canadian surgeons are for the most part very

pleased with our system and academic health care in

Canada is thriving.

THE MESSAGES

The four speakers described the Canadian health care

system with a focus on the academic health science centre.

We emphasized that the Canada Health Act ensured

Canadians of a system that is universal, portable, accessible,

comprehensive and publicly administered. Rich

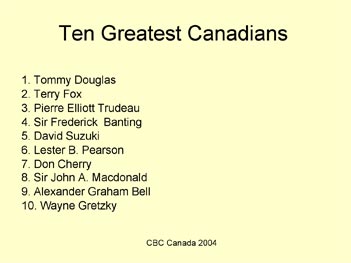

Finley commented on the fact that when polled on

who they most respected, more Canadians mentioned

Tommy Douglas, the father of Medicare, than any

other figure. Roy Romanow, in his 2002 report articulates

what many Canadians feel about our system: "the

principles of the Canada Health Act began as simple

conditions attached to federal funding for medicare.

Over time, they became much more than that. Today,

they represent both the values underlying the health

care system and the conditions that governments attach

to funding a national system of public health care. The

principles have stood the test of time and continue to

reflect the values of Canadians."

Our audience was especially interested in the differences

between the Canadian and the U.S. systems. We

acknowledged that those Americans who are insured

enjoy better and more immediate access to health care

services. Further, we underscored that repeated public

opinion polls increasingly have shown that the greatest

concern Canadians have about the existing publicly

funded health care system is the perceived waiting times

for diagnostic services, hospital care, and access to specialists.

But better access to services in the U.S. comes

at a dramatic cost. Some of these costs are easy to calculate,

such as the fact that we spend roughly 10% of

our GDP on health care whereas America spends 15%.

Some of the costs are more difficult to put a value on,

such as Canadians' immunity from financial devastation

if they become ill and the stark reality that 40 million

Americans are uninsured or under-insured. We spoke of

the costs of administering our health care system, which

are a fraction of the costs in the U.S. For example, most

Canadian surgeons have one secretary who does all of the

surgeon's billing as a small part of the job. In contrast,

it is not uncommon for an American surgeon to employ

three or more individuals whose sole job is to negotiate

payments with insurance companies and administer a

complex billing process. We were asked what our average

receipts were for every dollar billed. When we answered

roughly 99 cents on the dollar, our American colleagues

were flabbergasted. The American system is so unwieldy

that Blue Cross of Massachusetts employs more people

to administer coverage for 2.5 million New Englanders

than are employed in all of Canada to administer single

payer coverage for 27 million Canadians.

But does the American health care dollar buy better

health? The answer is essentially no. Gord Guyatt, in a

systematic review of studies comparing health outcomes

in Canada and the United States, examined 10 recent

"high quality" studies. He reported that of the ten, five favoured outcomes in the Canadian system, two

favoured outcomes in the American system and three were equivocal (4).

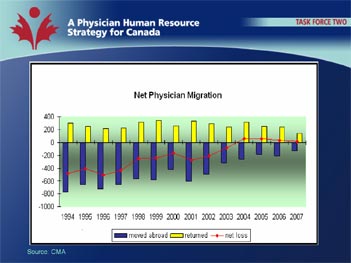

The myth that Canadian doctors are escaping to the U.S.

in droves still persists. I believe we dispelled that myth.

Data from the Canadian Institute of Health Informatics

show that the "brain drain" reversed in 2004. In 2001,

555 physicians left Canada whereas 334 returned. In

2004, 262 left and 317 returned and in 2005 185 left

and 247 returned.

|

We also addressed the issues of governmental involvement

in patient care. We emphasized that in our system

patients choose their own doctor and the government

does not participate in day-to-day care, nor do they collect

any individual patient information. We took pains

to indicate that everyone in our system receives the same

level of care. Finally we stressed that when polled 86 %

of Canadians supported or strongly supported public

solutions to make our public health care stronger.

|

A fair bit of the discussion was philosophical. We questioned

what the barometers were of a civilized society

and opined that one measure is the ability of a nation

to look after its sick. We questioned the right of insurance

companies to make large profits on the unfortunate

victims of illness. We underscored that Canada's health

care system, which fully looks after 32 million people,

costs roughly what the private-sector health insurance

companies make in profits in the United States. And we

talked of the medical mal-practice culture in the U.S.

compared to Canada. In the U.S. it is estimated that

court costs and judgments add 2 to 3% of GDP to the total medical tab (5).

|

Our American colleagues were stunned when we reported

the incomes of Canadian surgeons in the academic

sector. Without question, our surgeons are making a

much better living than they would as academic clinicians

in just about any American jurisdiction. With a

gross income of $335,000 (2006 CMA data), approximately

$100,000 in salary support for a new academic

recruit, a minimum of 20% protected time, average oncall

duties of one in six, virtually no time spent on sourcing

work, and malpractice premiums of $12,000 -- by all

measures, Canadian surgeons are doing well.

Finally, we discussed training and the looming HHR crisis

in both our countries. While both nations are under

the same strain with respect to physician shortages, we

are much better positioned to respond to this problem.

The root of the difference is the Balanced Budget

Amendment in the U.S. which has ostensibly thwarted

growth of residency programs. In contrast, Canada-wide,

the numbers of surgical residency positions has grown

from 1350 in 05-06 to 1550 in 08-09; an increase of

15%.

After one and one half hours of talks and a robust and

animated question period, the session closed. All five

of us, McLeod, Finley, Fitzgerald, Scully and Reznick

remained for a long time to accommodate individuals

who had additional questions for us. We were overwhelmed

by their interest, upset by the depth of concern

many expressed about their own system and immeasurably

proud to be Canadian.

Richard K. Reznick

R. S. McLaughlin Professor and Chair

(1)

http://thecaucus.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/08/18/death-panels- arent-the-half-of-it-says-senator-kyl/: accessed Nov. 9, 2009

(2) http://www.google.com/hostednews/canadianpress/article/ALeqM 5jRNEXbCDOJNCa_L56GCMqRDYehmw :

accessed Nov. 9, 2009

(3) www.hc-sc.gc.ca/hcs-sss/hhr-rhs/strateg/romanow-eng.php:

(accessed Nov. 8, 2009)

(4) Guyatt GH, Devereaux PJ, Lexchin J et al. A systematic

review of studies comparing health outcomes in Canada

and the United States. Open Medicine, Vol 1, No 1

(2007)

(5) http://network.nationalpost.com/np/blogs/francis/ archive/2009/05/12/health-care-lies-about-canada.aspx :

(accessed Nov. 9, 2009)

|