First Annual Balfour Lecture

in Surgical Ethics

“ MISTAKES HAVE CHANGED: 40 YEARS

OF WATCHING SURGEONS CREATE

ACCOUNTABILITY”

Donald Balfour

|

Donald Church Balfour,

1882 – 1963, received his

MD from the University

of Toronto, interned at

Hamilton City Hospital,

and studied surgery at the

Mayo Clinic. His father

was president of the

Balfour Tool Company.

Donald devised and introduced numerous instruments

– an operating table, operating room mirror

for teaching, an abdominal retractor. He married

Carrie, Will Mayo’s daughter, and spent his distinguished

career at the Mayo Clinic. He became

Chief of General Surgery and President of the

Mayo Foundation for Education and Research. He

received many honors and awards as a surgical educator

and scholar. His family endowed the annual

Balfour Lecture that celebrates his memory and

brings distinguished scholars in Surgical Ethics to

teach in our Department.

|

Charles Bosk

|

Charles Bosk is a distinguished

social scientist and a careful student

of the tribal customs, values,

and beliefs of surgeons. His

doctoral thesis in sociology was

based on 18 months of ethnographic

observation as an active

member of the surgical team

at the University of Chicago.

His publication “Forgive and

Remember: Managing Medical Failure” became a classic of the sociology and surgical literature.

(The following paragraphs are the Editor’s approximations

of direct quotations. They are not verbatim)

Professor Bosk’s areas of specialization as a medical

sociologist include professions and professionalization,

deviance and social control, field methods of research,

and the sociology of bioethics. He has three ongoing

funded research projects: 1) how ideas about safety move

from national policy-setting bodies formulate ideas about

‘safety’ that then move into administrative offices of hospitals

where they are converted into policies that are then

embraced or evaded on the floors where care is provided;

2) an ethnographic exploration of mandated duty hour

limits on graduate medical education, especially as it

impacts patient care and definitions of

professionalism; and 3) an intervention to

mitigate chronic fatigue in medical residents

through a mandatory nap program.

He is the author of “What Would You

Do?: Juggling Bioethics and Ethnography”;

“All God’s Mistakes: Genetic Counseling

in a Pediatric Hospital”; “Forgive and

Remember: Managing Medical Failure”;

and is currently working on a manuscript

“Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Medical

Error.”

“Administrative rhetoric shapes and

misconstructs the issue of surgical error.

The analogy to airline crashes is a very

poor fit that misleads our thinking. If the

analogy were carried to its logical conclusion,

it would help us deal with explosions

of hospitals with the death of all occupants. So, let’s

drop the airline analogy. It might be appropriate to think

of patients as baggage of different sizes and shapes, and the

challenge of medicine might be envisioned as the ability

to handle these well. We do better with the management,

delivery and safe-guarding of medications than the airlines

do with baggage. The handling of patients is a much a

larger and complex challenge.

“Quality improvement does not comport well with

patient experience. System error has displaced impairment

or incompetence of individuals. It is still true that

‘bad apples’ like Dr. Shipman in the UK require individual

responsibility, as a focus for management. Our

healthcare workers, a ‘vulnerable population’, are suffering

from safety program fatigue. New interventions to deal

with the challenges outlined in the Institute of Medicine

Report ‘To Err is Human’ include rescue teams, electronic

records for order entry, the 80 hour workweek and other

innovations. Fatigue errors are rare and, interestingly, the

80 hour workweek did not improve outcomes. 80 hours is

just 8 hours short of half a week, a long period of service.”

In Charles’s study of the 80 hour week, he found that

hospital computers were set so that they could not accept

more than 80 hours. This resulted in full compliance, an

imaginary accomplishment.

“Safety innovations have drained face to face interactions

and therefore have drained trust. Technology is

opaque, making problems difficult to identify and fix.

Interns involved in night float coverage,

a remarkably inefficient innovation of

the 80 hour workweek, go from a panel

of 10 patients during the day (3 sick, 3

safe, and 4 uncertain) to a panel of 60

patients as they cover 6 services on the

night float. That means 18 sick and 12

uncertain, an impossible assignment of

responsibility.

|

“System error tends to end the discussion

of most clinical errors. No one

feels responsible and there is no incentive

to solve system problems, which are

beyond individuals’ capability to change.

Similarly, checklists encourage mindlessness.”

In a gracious footnote, Charles

referred to his position as an observer and

commentator on the problems of surgery.

Quoting Mark Siegler, he said ‘I have the counterfeit courage

of the non-combatant’.

“Health is a public good that has been transformed

into a marketplace good. This creates a tension between

the ideal and the real. We need to correct the mistaken

assumptions embedded in policy solutions. Fools are

cleverer than system designers. It is difficult under current

dogma to determine what counts as a mistake.

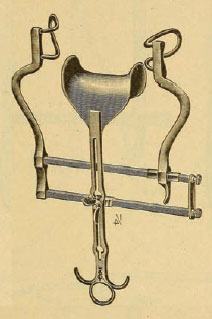

The Balfour retractor, for many years a

staple of abdominal surgery

“There is a lesson to be learned. The job of residents

is physically and cognitively demanding. Residents are

required to make decisions under time pressure, with

incomplete knowledge in the presence of uncertainty.

This leads to errors and adverse outcomes, but error is an

essentially contested concept. We cannot define it out of

context. Residents can only use tentative reasoning in the

presence of uncertainty. If A is true, then B may be the

best decision in this setting. [If A cannot be known at the

time a decision is required, defensible errors can follow.]

“We need to look at health policy on the street level.

The IOM Report of 1999 used an unfortunate model –

the body count model, where there are 44,000 or 86,000

or 98,000 deaths in the healthcare space caused by error.

The goal to cut the number in half by 5 years involved

technology, such as electronic order entry, the electronic

record, the 80 hour week, and various other system fixes.

The ‘To Err Is Human’ Report has led to ‘techno – vigilance’

in the United Kingdom, and technology solutions

in the United States. The solution is not more robots, we

need more discussion of surgical judgement.

“In medicine, death occurs related to the pathophysiology

of disease. In surgery, it does not result from the

pathophysiology of disease, because of surgical agency to

interrupt the pathophysiology. In medicine, when a patient

dies, colleagues ask: ‘What happened?’ In surgery, when a

patient dies, colleagues ask: ‘What did you do?’ The challenge

for the future is to align the experience of the patient

with the experience of the surgeon, and to curb the enthusiasm

of surgeons and patients for operations that defy the

odds and result in miracles. The value of the ‘time-out’,

even though it seems counterintuitive for each individual

to say their name prior to the surgical operation, is that it

enables people to speak when a later challenge occurs. We

need to punish those who do not speak out.

“In the post Greenspan era, we have been taught to think

differently about return on investment. Return to capital is

perceived as progress. Return to labour is seen as inflation.”

Charles’ goal is “engaging people’s understanding

of what they are doing”. He is an enthusiastic student

of the great sociologist Elliot Freidson, author of the

“Professionalism; the Third Logic”, a thought-provoking

critique of the notion that the market or corporate

structures like governments or institutions can provide

adequate logics or conceptual frameworks for civilization

to flourish. His Balfour lecture on Surgical Ethics

was a highly praised demonstration of the importance

of Professionalism as a guiding framework for addressing

important challenges faced by surgeons.

M.M.

|