International Surgery: Challenges and Responses

"Most people on the planet who need surgery can't get it.

Changing this surprising situation is a challenge to which

universities should rise - to solve the problem or to train

people who can solve it. As an academic health science

faculty, we cannot provide health care for Canada, much

less the world. We don't build healthcare infrastructure, but

what we can provide is training." - Andrew Howard

In 1999, John Wedge and Massey Beveridge founded the

International Surgery Office within the Department of

Surgery, and Andrew Howard joined the enterprise. He

now serves as Director of the Program. Andrew has had

a long interest in surgical education and surgical care

in Africa. He has a mandate to study injury control in

African children. In this resource constrained setting, the

infrastructure required for care and research is severely

limited.

There is a long and distinguished history of Canadian

participation in International Surgery, dating back to

Norman Bethune, a University of Toronto graduate

and hero of International Surgery in Spain and China

Canadian Cardiac surgeon Lee Erett won the Norman

Bethune award from the Chinese Government for operative

teaching and practice in China (see also http://www.surgicalspotlight.ca/Shared/PDF/Spring07.pdf ). For

many years, our surgeons have been going to where they

were needed and treating grateful patients, regardless

of their ability to pay. Readers will be familiar with the

problems of HIV, tuberculosis and malaria in Africa, but

there is a less well-known problem- the severe deficiency

of surgical care. 13% of Africans die from trauma and 1

in 13 women die in childbirth.

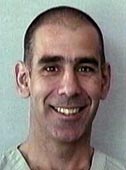

Andrew Howard with his wife, Lianne and their two daughters, Emma

and Samantha

The service needs overwhelm capacity. There are

only 400 surgeons in all of East Africa. Most are very

busy. They do private work to support themselves and

provide care in the public system, leaving little time

and no financial support for teaching. The University

of Toronto psychiatry program led by Clare Pain provides

a very effective model. They have worked with

psychiatrists at the Addis Ababa University in Ethiopia.

Ten years ago, there were no residents. They now have

a functioning residency and have raised the number of

practitioners in the country from 3 to over 3 dozen.

Based on this example, Ted Gerstle is developing a similar

program in pediatric surgery, and Andrew is trying to

do the same in Orthopaedic surgery.

The Office of International Surgery provides electronic

access to the University of Toronto library, so surgeons

and other healthcare personnel in Africa can share

our textbooks, journals and other subscription- based

services. The librarians who have made this possible

are Sandra Kendall at Mount Sinai Hospital, and Sian

Meikle and Warren Holder at the Robarts Library. The

Office of International Surgery provides the services to

several hundred surgeons in Africa and supports librarians

in Africa to facilitate their use.

The College of Surgeons of Eastern, Central and

Southern Africa (COSECSA) is a certifying body that

has developed surgical training programs (see also http://www.cosecsa.org/). The College approves training by

skilled surgeons at busy community hospitals as well as

university sites. There is an online course with a tutorial

to help candidates pass the College exams (see http://www.ptolemy.ca/members/). The entries are developed

by African surgeons in combination with a Canadian

author to provide an international perspective. Some

of the work on this project has been published in the

Canadian Journal of Surgery. The training process is

somewhat like the British system. There is an early

exam, analogous to the British Fellowship exam or our

Principles of Surgery Exam, followed by specialty-specific

training in various disciplines such as paediatric surgery,

urology etc. Canadian surgeons provide examiners,

but also develop curricula and travel to Africa as teachers.

When I interviewed Andrew, he had just returned

from giving exams in Uganda for COSECSA.

Andrew was born in Edinburgh, grew up in High Prairie

Alberta, completed his undergraduate medical training

and surgical residency at Queens, followed by a fellowship

in Orthopaedic Surgery at the Hospital for Sick

Children. His wife Lianne and two daughters Emma and

Samantha accompany him on his paddling and skiing

forays into the Canadian wilderness, and they are looking

forward to travelling to Africa together one day.

The Office of International Surgery has brought surgeons

to Toronto to study. For example Milliard Derbew

spent a sabbatical year at the Wilson Centre, studying

Surgical Education (see also the Surgical Spotlight, Spring

2006, page 9, or go to http://www.surgicalspotlight.ca/Shared/PDF/spring06.pdf). He subsequently became

Dean of Medicine at Addis Ababa University. There is a

striking need for paediatric orthopaedic surgeons in Africa,

given that almost half of the population is less than

15 years old. Andrew's hope is to develop a Canadian

Community of Interest in Surgery in Africa. "We are at

a very early stage, but the Surgeon Scientist and Surgical

Education Program grew from a small group of interested

surgeons to major themes in our department."

|

UNIQUE APPROACHES TO THE CHALLENGE

Alex Mihailovic

|

Alexandra Mihailovic is a Critical Care fellow who

completed our general surgery residency with a focus on

trauma. Her critical care program includes 13 months of

core training in various disciplines, including transplantation,

medicine, surgery, and seven months of trauma

training in Cape Town.

The experience in Cape Town is enlightening and

intense - four to five thoracotomies or laparotomies per

day, largely for gang - related injuries in the townships -

"When a patient has been shot and there are 4 bullets on

the chest X-ray, it's impossible to tell which are today's

bullets. It's difficult to record outcomes in this population

as most of the patients will never return for follow

up once they've left hospital. The sanctity of life is less

cherished. When a 22- year old dies in the operating

room, the staff comforts the surgeon saying: 'He probably

killed five people today before he was shot'. Some

staff are resentful of putting

multiple units of 'our blood

into this killer'."

Alex worked with Neil

Lazar in the medical ICU

at UHN. She became very

interested in ethics and social

determinants of illness. "In

Africa, there is little investment

in prevention of trauma

and therefore no reduction

in the cost of patching up the surviving victims." Alex is

a PhD candidate, studying the epidemiology of trauma

in Uganda. Andrew Howard is on her committee. She

also spent two months in Haiti, as the only surgeon at

the time she was there, treating victims of the earthquake

and the results of displacement post earthquake with the

Canadian and German Red Cross.

One of the striking problems in Haiti was the intervention

by doctors from NGOs, who performed elective

operations in addition to emergency care. This was

encouraged by many NGOs, because they provide the

opportunity for publicity photos. However, diverting

patients to a free elective surgical service deprives the

local surgeons of the fees they need to buy food and

maintain their lives in Haiti. "There is a danger that

NGOs might eventually force the local doctors to move

to Miami or elsewhere in order to make a living. I felt

more like a culprit in this situation, as the local doctors

said: 'I can't feed my children if you visiting surgeons do

the hernias, gall bladders and cesarean sections'."

Alex found a middle ground, debriding ulcers, rotating

flaps, treating burns, operating only on inpatients

and emergency cases to keep her out of the elective

schedule. The ethical quandary after surgery is - "where

do these burned patients and paraplegic patients go?

People in wheelchairs can't travel where there are no

roads and often there are no rehabilitation or prosthetic

services available to help them gain independence

again...so after all that work to get them surgically

healed you then are left with a patient you can't discharge

into the streets."

Georges Azzie

|

HSC surgeon Georges Azzie focuses his practice of

international surgery in a setting where he was initially

employed by local authorities (Botswana) and

where he knows and understands the environment.

Programs he has helped foster

are based on local needs

assessments. Georges helped

develop a multi-facetted program

to develop laparoscopic

skills among surgeons. This

included (but was not limited

to) yearly workshops, a

telesimulation program done

in conjunction with Allan

Okrainec (see also Surgical Spotlight Winter 2009) and ongoing support at multiple

levels. [There is an interesting response to this

important contribution to international surgical education:

Some program directors from higher income

countries object to teaching minimal access techniques

to local surgeons. They send their residents to Africa to

perform open operations as surgical tourists. "Where else

can they get this experience?" - Ed]

Georges' experience leads him to minimize the

destructive side - effects of "surgical tourism" in low

and middle income environments. He is "the first to

admit that he has more questions than answers with

regard to addressing the global burden of surgical

disease and to mentoring those with similar career

interests."

|

The 11th meeting of the Bethune International

Surgery Round Table will be held in Montreal,

June 3rd, 4th and 5th 2011 (http://www.cnis.ca/what-we-do/public-engagement-in-canada/bethune-round-table/). Eight of the previous meetings

have been held in Toronto. The round table draws

surgeons from Canada, South America, South East

Asia and elsewhere to teach and learn about international

surgery.

|

M.M with notes from Andrew Howard,

Alexandra Mihailovic and George Azzie

|